The self is absolute, non-negotiable need. We might think otherwise – in fact we do think otherwise – but under all the various layers of camouflage there is nothing else to the self other than raw irreducible need.

The self disguises its true nature because raw need is not a very palatable prospect! It doesn’t look very good, either to me or to anyone else. Raw need isn’t a pleasant thing to encounter and to avoid this unpleasantness the self has adopted very many strategies, all of which come down to the same thing in the end – validation.

Need is an unquenchable hunger and hunger is an absence, a deficit. It is not anything positive at all, no matter how you look at it. This is too terrible, too dreadful a truth to admit to for the self and so it cloaks itself in various garments (various identities). It is this, or it is that, or it is the other. The self pretends to be very many different things all of which can be seen to be wholly nonsensical, wholly absurd, when we look at them closely enough.

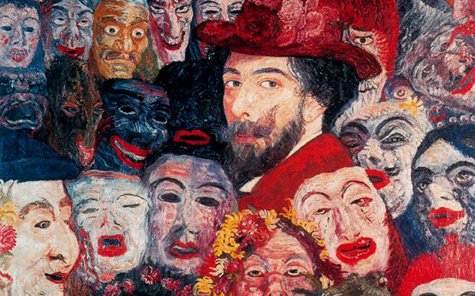

The self hides behind very many different masks and these masks are all ultimately quite nonsensical. Obviously a mask is ultimately nonsensical – it is only a mask. If nonsensicality of the self’s mask were to be seen then clearly it would not get very far in its pretence. If we could see that the self’s masks are ultimately absurd then there would be no comfort – no ‘escape’ – to be had in wearing it and so to make we can’t see this truth the self has a trick up its sleeve. What the tricky self does is that at the same time that it hides behind the mask it spins a kind of illusion within which this mask is meaningful rather than meaningless, serious rather than ridiculous, important rather than absurd…

This is the self’s game and as long as we can’t see through the game then we can’t see the absurdity of the mask. The mask has the same relationship to the game of the self that winning or losing has to a game of football – if we don’t take football seriously then neither winning or losing mean anything and if we don’t the game of the self seriously then we don’t take the mask of conditioned identity seriously. The mask means so much in the game – it means everything – but when we give up playing the game it means nothing at all.

The most significant thing that we can say about the illusion game spun by the deficiency which is the self is that it is shallow. The defining characteristic of games is that they are trivial, limited, superficial. If they weren’t trivial, limited, and superficial then they wouldn’t be games. So when we look at the world in the trivial, limited and superficial way that the game insists upon then we can’t see how ridiculous the self’s masks are. Instead of seeing these masks as being nonsensical we see them as being we worship them, we adore them, we idolize them. The self’s deception goes unnoticed, its camouflage is complete, its disguise wholly convincing.

What the self is hungry for is being, and all of its disguised are pretences at being. being is what the self wants more than anything, for the simple reason that this is what it can never have. The self is a lack of being, a deficit of being, and this lack or deficiency is the root of its absolute, non-negotiable need.

Even though the self can never obtain the prize of being for itself, it can kid on to itself (and its audience) that it has being a plenty, being in abundance, being in spades, being of the very highest quality. The main tactic which it uses to pull off this deception is to assume that it does and then act accordingly. By making this assumption and then refusing to ever think about that fact that it has done so, the self creates for itself the illusion of being. All that it needed in order to keep the illusion going strong is that it should never check up on this assumption, that it should keep on taking it for granted. This taboo on looking too closely at what lies behind its own assumptions is the first rule of the game of the self. The possibility (or rather threat) of finding out the truth is what the self knows as fear.

Another, related tactic that it uses is to persuade others that it has being and then use the admiration or envy of these gullible on-lookers as proof of the fact so that it can then be all the more secure in its own lies. This is the so-called ‘status game’ which almost everyone plays in one form or another. And the thing about the status game is that it doesn’t matter how well you play it because wherever you come in the ranking it still re-affirms the validity of the game that is being played. Even being the bottom of the pile still affirms the central illusion that the status of the mask is important, which is to say, that the mask or ‘conditioned identity’ is real!

In this game we play for an identity that will be highly regarded by others as well as ourselves, we play for a ‘good name’. This means that it’s all about the identity, all about the name – I am intensely attracted to the possibility of achieving a good name and intensely averse to the possibility of being stuck with a bad one. The former scenario makes me feel great, the latter makes me feel terrible. But no matter what happens, no matter whether I feel great or terrible, it all goes to reinforce the central idea that it’s all about the identity, that its all about the fixed or static representation of ourselves, which is actually the denial of who we really are. In competing for a limited (and therefore ultimately absurd) mask to be identified with we are necessarily turning our backs on who we really are, and so to succeed at this game is to ‘lose’ in a tremendously more important way. I succeed at something meaningless and the price of this trivial (or superficial) victory is that miss out on what really matters.

The success of the self in the game of pretending to have actual being, actual substance, is quite sterile, quite meaningless. All it succeeds in doing is in creating a desert that it cannot see as such. What it succeeds at is not in achieving being – because this is the one thing it can never attain – but the plausible deception of possessing being, both to itself and others. Thus, what it succeeds in creating is a pointless, sterile situation that it cannot see as being pointless and sterile.

Ideally, what I would like to do is to manufacture the outwards appearance of a fulfilled and happy life so that everyone can look at me and envy me this happiness. If I manage to pull this off then I won’t actually feel happy inside because the outwards or theatrical appearance of happiness does not result in the genuine article and yet I am bound to think that I must be happy and fulfilled since everyone else is convinced that I am. I am holding onto the illusion of happiness therefore, the name of happiness, and this illusion or name has to substitute for the real thing. It will have to serve, it will have to suffice.

As long as I am able to believe in this illusion then I will at least be able to obtain some limited satisfaction out of it, although this satisfaction is very poor fare indeed when compared with the real thing. Illusions are by their very nature unsatisfactory – they are inherently unreliable and insubstantial. Trying to squeeze happiness out of an illusion, out of a name, is like trying to warm my hands on a cold winter’s day in front of a picture of a roaring fire. It might be a very good picture, but no matter how good it is it still won’t produce even the tiniest morsel of warmth. A superior quality picture is exactly equal to an inferior one in this regard!

In the same way the self tries its best to warm its hands on the glory of its mask, which at the best of times is a cruelly unsatisfactory business to get caught up in. It is no wonder that the conditioned identity is prone to so many different types of upset and distress. Its ‘happiness’ is a very fragile and brittle thing indeed – it only works (if we can go so far as to use that word) when everything is exactly in place, when all the supporting factors are lined up exactly right, and this requires a tremendous amount of controlling and ‘environmental manipulation’ on the part of the poor conditioned identity. And even when this huge investment in control has been made things are only going to be right from time-to-time, at the very best. So the conditioned identity, my sense of me being this particular fixed or static mental image, spends only a little time feeling the brittle type of ‘pseudo-happiness’ that is the only type of happiness it is allowed to feel, and all the rest of the time going through many different types of unhappiness. This – needless to say – does not sound like a particularly great deal.

The problem is that I am led on by the promise of happiness, which not only looks very much better as a promise than it ever turns out to be in real life, but also carries the additional promise that it won’t turn out to be tormentingly transient, but – if I get my controlling right – totally solid and permanent, ever-lasting and imperishable. This is the lure, this is what sucks us in. The reality as we have said is very different from the promise – the euphoric high, far from being ever-lasting, is fleeting, and is always followed by the flip-side of the coin, which is the dysphoric low.

The type of mental suffering that the conditioned identity is obliged to endure is the type which we are more familiar with under the heading of ‘neurotic mental illness’ – neurosis is the price, not just of civilization, but of the fixed and limited identity. The mask, the fixed identity is like a turning wheel or disc, and the state of being we crave, the situation where ‘everything is right’, is like one specific position on this turning wheel. As the position comes closer the feelings of pleasurable anticipation grow but no sooner has the location on the wheel reached the reference point, than it is moving off again and getting further and further away with each passing moment. No sooner has the desired situation arrived than it is moving off again!

This gives us the first and most basic form of neurotic distress, the distress of trying to hold onto pleasure as it passes. The greater the intensity of the euphoria we experience the greater the let-down when it escapes us again – it is our nature to keep going for progressively more intense highs, but the degree of pain that follows the high exactly correlates with the degree of the pain of the ‘come-down’ and so the net gain is zero. Pleasure thus turns into the torment of frustration, and all we can do is keep hitting the button and – in the process – keep subjecting ourselves to the frustration of having it slip away from us each time. We chase the highs and suffer from the low, and since every up comes with a down the net gain of the exercise – as we have said – is always zero.

Just as we can say that the optimally advantageous position is where everything is everything is ‘lined up just right’, so we can say that the optimally disadvantageous position is where everything is arranged in a way that is exactly wrong. This is the shadow-side of getting it right – if there is such a thing as getting something exactly right then it must also be the case that we can get it exactly wrong too. The one type of certainty cannot exist without the other. So we could also say that there is another position on the rotating wheel of the fixed identity which correlates to the situation of ‘obtaining the undesired outcome’, so just as much as we want to obtain the state of mind that correlates with our situation being right, we want desperately to avoid the state of mind associated with it being wrong.

Approaching the maximally disadvantageous situation, and experiencing negative anticipation towards it, is better known as anxiety. Whether it is true that we really are approaching our own ‘worst case scenario’ or whether we are just so frightened of this happening that we are unrealistically imagining that we are makes no difference at all since it is the fear of the unwanted eventuality that counts, not the reality of what is going on. Because we know – even if we don’t want to – that the worst case scenario is on the cards just as much as the best case scenario, the spectre of anxiety has entered the picture. We can’t therefore say – as we generally do – that anxiety is an ‘unrealistic’ fear – because inasmuch as there is a fixed or determinate identity (a ‘self’) there must be such a thing as a maximally disadvantageous situation just as much as there is a maximally advantageous one. Because the self is a fixed point of view the situations that might be encountered in the world are automatically divided – from this determinate standpoint – as being either ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. From the self’s perspective, therefore, everything is about winning or losing, succeeding or failing.

‘Good’ and ‘bad’ are projections of the fixed self – the former is where there is a fulfilment of its absolute non-negotiable need, and the latter is where this fulfilment does not take place, and the need is unsatisfied. GOOD equals the self just as BAD does, and this means that the self equals ‘a euphoric high’ just as much as it equals ‘a dysphoric low’! Alternatively, we could say that the self equals ‘advantage’ just as much as it means ‘disadvantage’ (there can of course be neither one nor the other without the self!), but as soon as we say this we can’t help seeing the utter contradiction of it all, we can’t help seeing the utter contradictoriness of the self!

Essentially, the inherently self-contradictory nature of the self comes down to the paradoxicality of certainty, the paradoxicality of the definite statement. Certainty equals YES just as much as it means NO – it means YES and NO in equal measure! How after all could we have the certainty of being able to say YES about something without at the same time having the certainty of also being able to say NO? The illusion that keeps the self going however is the preposterous illusion that this actually IS possible! Or to put this another way, the illusion that keeps the self in business as a viable proposition is the illusion that it is possible to be susceptible to being flattered (i.e. to be given a good name) without at the same time being every bit as susceptible to being insulted, to being given a ‘bad name’…

Image: Self-Portrait with Masks (1899) by James Ensor.