The danger of machines lies in their specificity, which is not at all an obvious statement to make. This isn’t an obvious statement because the only reason machines are of any use to us (the only reason machines get to be machines) is because of their specificity. We can hardly object to machines or technical systems being targeted towards specific outcomes therefore – that would be entirely unfair!

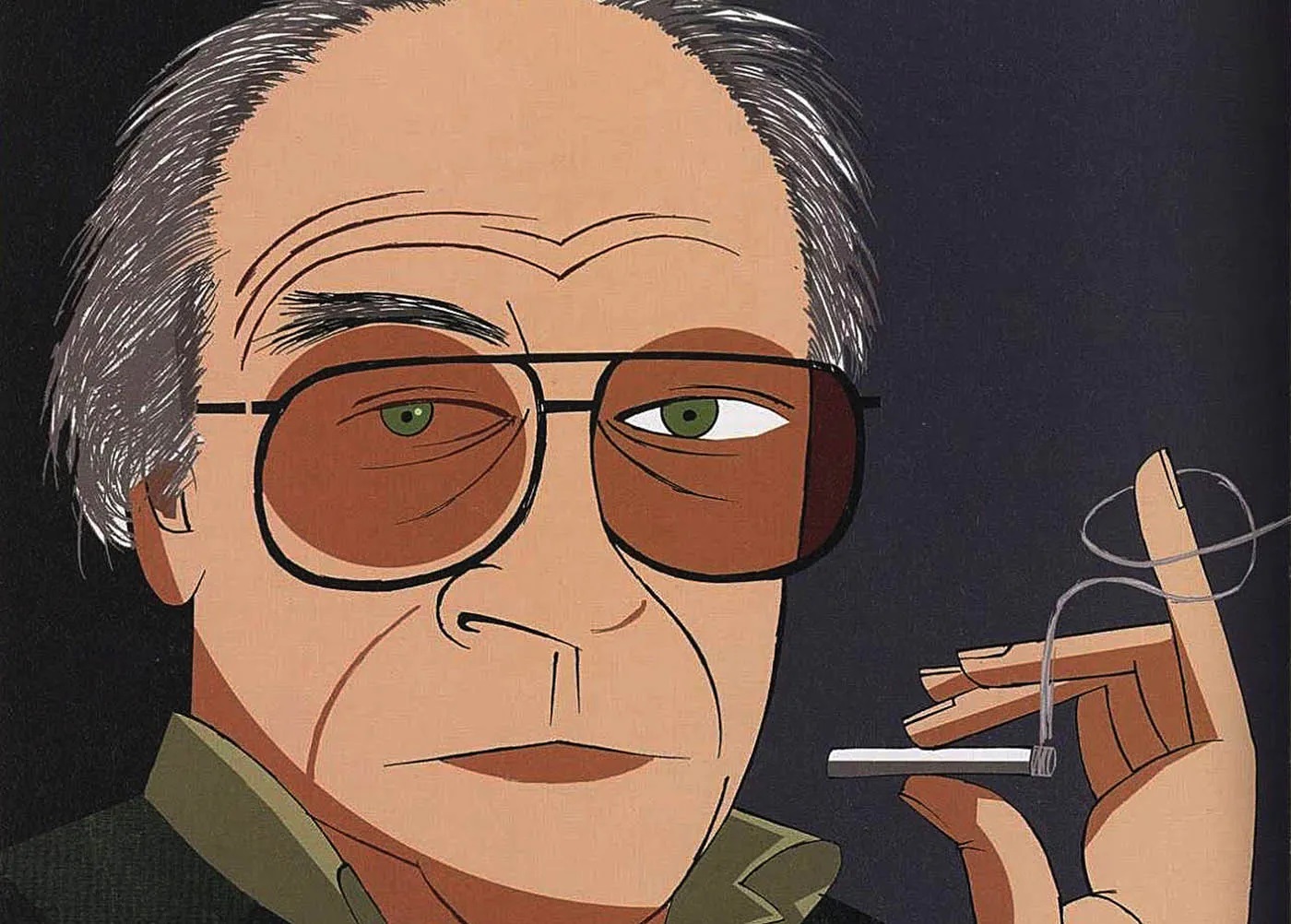

Saying that machines are a danger because of their specificity doesn’t tend to make much sense as a statement when we first hear it, particularly since we live in a society that is based on mechanisation and has been for a long time now. This is however simply because we’re not seeing the full picture – we’re not taking a broad enough view of things to see to be able to see where the problem is. The ‘problem’ that we’re talking about has been highlighted with great vividness in the field of philosophy by Jean Baudrillard, but (with the possible exception of the French) we’re not really in the habit of taking philosophers seriously; Philosophy has nothing to do with anything else with life itself as far as we’re concerned; It has nothing to do with anything apart from philosophy and so we don’t really care about it – we keep everything in nice neat compartments, compartments that we never go beyond.

Baudrillard talks about the situation where our ideas about things (or our ‘mental representations of things’) all join up together and ‘hold hands’ so as to become one big virally reproducing self-consistent system of mental representations that block out or exclude any trace of reality itself. Instead of unformatted reality (which is not a self-consistent system of logic) what we have instead is a virus programme which is involuntarily shared between us and which totally determines how we understand and perceive the world. This is what Jean Baudrillard calls hyperreality – hyperreality is a highly virulent oversimplified or stereotyped ‘pseudo reality’ that feeds on itself and – in this way – does away with the need for unformatted reality. The artificial production becomes everything. If we have a nice straightforward idea about things, who wants reality getting in the way, messy and unruly as it is? When we have an orderly or regular accounting system setup, anything that doesn’t fit into the system is an irritant and nothing more. It’s an irritant that only inspires one thing in us and that is the desire to get rid of it.

That then is hyperreality – the replacement of the real by the representation. Just as we can say that any discrete representation is itself not a danger just so long as it is visible as a representation, so too we can say that it is the case that machines and mechanical processes aren’t a danger to us just so long as we can see them for what they are. This is not an obvious point – when we talk about machines we’re not just talking about isolated mechanical devices (i.e. we’re not just talking about any particular machine) but a ‘sphere of influence’ that is far more extensive and pervasive than we ever could have imagined. As James Carse points, out we can’t use machines unless we adapt ourselves to the machine’s ‘view of the world’ – which is to say, we can’t use machines unless we learn to think like them. When almost all aspects of our life are being run by machines – bearing in mind that the infrastructure of the digital media systems that we rely on so much is also ‘a machine,’ and that the world that the digital media system creates for us is an output of a machine, this inevitably means that we’re going to spend most of our waking lives having to think like machines ourselves. The sphere of influence that we’re talking about here isn’t just extensive – it’s very nearly total. Because we have embraced mechanization unconditionally we ourselves have become mechanized in the process.

Suppose that we are prepared to accept, however provisionally, that the world which we now live in is digital in nature (since it is mediated by information technology) – we might then ask why this constitutes ‘a danger’? Why is a digitally-mediated reality more specific (and therefore more dangerous) than the original analogue-type reality? If we did ask this question then we would have stumbled across the root of the whole thing – just as machines can never be unspecific with regard to their output (since the output is implicit in their design) so too must all digital outputs be ‘certain’, which is to say concrete or literal. The digitally-mediated world is always concrete in other words; It is always concrete because it’s based on rules or algorithms and rules / algorithms are quintessentially concrete, quintessentially specific. How could the rule not be specific after all? A rule says what the rule says and that is the end of the matter – there’s no way that it can be coaxed into being metaphorical or multivalent. We can try to devise digital processes that give rise to shades of meaning or a number of different meanings at the same time, but this is never going to be any more than a trek dash it’s never going to be any more than the trip because all we are doing is producing a series of literal meanings with which we are attempting to mimic the non-literal, or metaphorical. It might seem to be going somewhere interesting and undefined perhaps, but really it isn’t. It’s a trick, a gimmick. The output of a machine can never be non-literal.

This is the one thing a rule or a machine can never do therefore – it can never give rise to a genuinely multivalent reality. A rule is a collapse of possibilities – it says what something is and once it has said what that ‘something’ is it has been nailed down forever. Once we say what something is then we can never go back, we can never go back to where we started off from again; we can never ‘work backwards’ from the defined location which is ‘the destination’ to the undecided or undefined state that was our origin. The literal statement of fact doesn’t contain the information that would be necessary for us to go back to – if it did contain that information then it would no longer be a literal statement of fact! This is a confusing point to try to make (or understand) when we’re looking at things in a machine-like way because when we’re looking at things in a literal way then there’s no such thing as an ‘undecided’ or ‘undefined’ possibility. If a possibility isn’t decided or defined then it doesn’t exist and so the whole question of what we have lost as a result of our reliance on ‘concrete statements of fact’ does not arise. Something has been lost, but we are – when we’re in the Mechanical Mode – utterly incapable of relating to that loss.

Reality has been murdered, but we are incapable of bearing witness to this crime, if we are to speak in Baudrillardian terms. This is an old, old story – we have been unceremoniously evicted from Paradise and now – in our fallen state – we are quite incapable of having any relationship whatsoever with this ‘Prior State of Being’. We’re incapable of knowing what is really meant by the term ‘Paradise’. We will continue to use the word perhaps, but now we understand it in a concrete or literal way, and because of this degraded form of understanding of ours we are all the further away from understanding the true nature of what has happened to us, of what we have lost as a result of our ‘falling into literalism’. It is our literal belief in the concrete ‘statement of facts’ that we make about the world that prevents us from seeing the actual reality, and this is why being an adherent of a literal or dogmatic religion is actually to be involved in the denial of the Divine, despite the fact that this may sound rather odd. Unless something can be concretely stated or literally expressed then it doesn’t exist we say (when we are in MM) and this implicit attitude of denial of ours is an expression of our loyalty to the machine, our loyalty to the rule. It is an expression of our loyalty to the machine because the concrete statement of fact (the ‘literal statement’) is the machine – the machine is a system of literal meanings, a system of meanings that imprisons us, and to which we feel loyalty.

Instead of saying that ‘when we are in Machine Mode we firmly believe that unless a possibility can be specifically defined then it can’t exist’ (or ‘can’t be a possibility’), we could say that when we’re in MM then we can’t relate to anything as being ‘real’ unless we can think it. We can only believe in our thoughts in other words, although we can’t see this to be the case since we can’t tell the difference between reality and our thoughts about it in the first place! Our thinking is the machine therefore and the world it shows us is the machine world. When we talk about our very close relationship with technology as having the unforeseen result of causing us to be defined by the technology that we ourselves have created we need to be aware that this technology is an extension of our thoughts and not anything else. It’s all the System of Thought, as David Bohm says, and this means that we are, in our daily lives, in the position of being sandwiched between ‘the machine on the outside’ (i.e. the digital environment) and ‘the machine on the inside’ (which is the thinking mind). Our thoughts are conditioned by the Designed World within which we live, and this Designed World is the extension of our thoughts and so the whole thing is a loop, a loop-that-we can’t-see-to-be-a-loop, a loop that feeds on itself.

The danger of machines is that the machine on the inside will join up with the machine on the outside with the result that – as far as we are concerned – there isn’t nothing else. Because there is (for us) nothing but the machine we can’t see the machine to be a machine and so the System of Thought and its productions substitutes for reality. The other way of putting this is to say that we have plunged into the Realm of the Hyperreal– we’ve been cheated and we can’t for the life of us see that we have! Everything has been converted into ‘the specific’ and so the specific now seems like ‘the thing’ to us – it is in the Realm of the Specific (or the Realm of the Particular) that we are going to look for all the ‘good stuff’, whilst the Unstated Realm – which is where all the good stuff really is – is forever off limits to us. Actually, there is nothing good (in the sense of ‘Wholesome’) in the specific at all! There’s nothing to be had there, nothing at all, and to believe that there is (to believe that they are actual possibilities there) is to be lost in this loop of illusion that is constantly feeding on itself.

Art: (open source art) taken from thecollector.com