To the Western ear Daoism sounds worryingly passive – we go along with the way things themselves want to go rather than calling the shots ourselves. We are sensitive to ‘the way things actually are’ rather than having some kind of super-important ‘vision’ or ‘view’ for the way they ‘ought’ to be…

To our Western sensibilities the important thing is our ability to obtain the goal (rather than our ability to stay in the uncertainty of not knowing what is happening) – if we’re not approaching a goal then we’re going in the wrong direction, if we’re not getting closer to the designated outcome then this equals (or so we say) ‘being passive’. Movement towards the unknown is therefore of no interest to us, no value to us.

This shows up our collective rational blind spot very nicely therefore – the blind spot in question has to do with our inability to see the significance of relating to things as they are in themselves (as opposed to how we’d like for them to be). We will say that we are interested in ‘the way things are’ of course (since it is only by having the correct information, the correct view, that we are able to control effectively) but this argument has a great big hole in it! It has a very big hole indeed in it, a hole that we never stop to notice.

The problem we don’t want to see is that whenever we obtain information with the aim of doing something with this information then our (so-called) information is going to be skewed, is going to be distorted (and therefore deceptive). The aim is colouring what we see as being ‘information’ or ‘not-information’ in the first place; as long as we have an agenda there in the background then this agenda is going to determine what we consider to be relevant or irrelevant and we are – by the very mechanics of this situation – always going to ignore what we see as being irrelevant. We will ignore it without knowing that we are. We are ‘ignoring by default’.

This is of course a very familiar principle in quantum physics – the assumptions we make in order to make our measurements determines what these measurements are going to be. Our viewpoint determines our view. The whole thing about making assumptions is that we DON’T examine whatever it is that we are assuming – that’s what ‘assuming’ means, after all – it means that we don’t bother to do any examining. We skip that bit to save time…

We can’t measure anything (or investigate anything) without making assumptions which we are automatically going to be blind to and so if these (necessarily invisible) assumptions condition what we find out to be true as the result of our investigations, what we discover as a result of the measurements we have taken, then this puts us in a very strange situation! We won’t see it to be strange (or in any way ‘suspect’) but it is, in a big way. Our situation is actually totally laughable – we oughtn’t to take it seriously, but we do. We are engaging with our own productions as if they weren’t our own productions, and this isn’t going to end well.

We perceive it to be the case that we are discovering something about the way things are in themselves whilst this is entirely untrue – the so-called reality that we are encountering is actually our own projection. We think we are learning something (or ‘expanding the remit of our awareness’) but the invisible truth of the matter is that we’re moving ever deeper into delusion. We are departing from reality, not ‘encountering’ it!

There is a hidden error in our view (or understanding) of things and this error is ourselves! If we’re in the picture at all as the so-called ‘objective observer’ then we are not going to be able to see reality at all, only the reflection of our own unexamined assumptions. As Jung says, what we take to be ‘the world’ is nothing more than our own unrecognised face looking back at us. The observer is thus what David Bohm calls the ‘systematic error’ – the error that can never be detected by the system itself. The system cannot detect the error because the system is the error. To itself it isn’t ‘an error’ of course; to itself the system is ‘the only thing that matters’ – on the contrary, it is ‘the gold standard’, it is ‘the measure of everything’.

This is maximally perplexing for us, of course. It couldn’t be more perplexing. The whole point of ‘investigating reality’ is to obtain authentically true information about it – information that can be used as the basis or foundation for our purposeful activity. But if we then learn that there is an error in the mix and that the invisible error is the independent observer, the investigator, the purposeful doer, the ‘agent’, then what does this insight do to our way of seeing things? What can we do with this highly unexpected bit of information, how are we to process it?

The only way we could ever see the true picture of ‘how things are in themselves’ would be if we weren’t looking at the world with some kind of aim in mind, would be if we weren’t wanting to ‘do something’ with the information thus obtained. We would have to look at the world in a ‘non-attached’ way in other words, which is by no means as straightforward as it might sound. Is not as straightforward as it might sound because it involves me dropping my habitual viewpoint – the habitual VP which is ‘myself’. I (as the separate observer or doer) is ‘the error which needs to be eliminated’, after all!

Being effectively purposeful the whole time sounds great to us Westerners but what it really means is ‘perpetuating our delusions’. Our goals are our delusions – our goals are necessarily our delusions since they only come about a result as a result of [1] – making assumptions and [2] not paying the slightest bit of attention to either ‘what these assumptions are’ or ‘the fact that we have made them at all’. Our bias towards only valuing our goals and goal-orientated activity is at root an indication of our lack of curiosity about what reality actually is in itself, therefore. It is an indication of our ‘investment in unreality’.

We aren’t interested in what things are in themselves but only in what we can make of them, and the problem with this is that what we make of them (or what we want to do with them) isn’t actually a real thing! It’s only real with respect to our assumed (or imagined) viewpoint. Seeing what we call ‘being passive’ as evidence of a lack of responsibility is an inversion of values therefore – we are valuing our delusions over reality itself. The passivity which we abhor so much actually means ‘passivity with regard to the unacknowledged act of denial that we are all involved in’. It is passivity with regard to this sneaky business of ‘taking part in a game that we do not ever admit to be a game’. What we call ‘being passive’ means allowing ourselves to be actually conscious, in other words, and if we ever were to do this then we would be accused by all and sundry of ‘letting the side down’ in a big way…

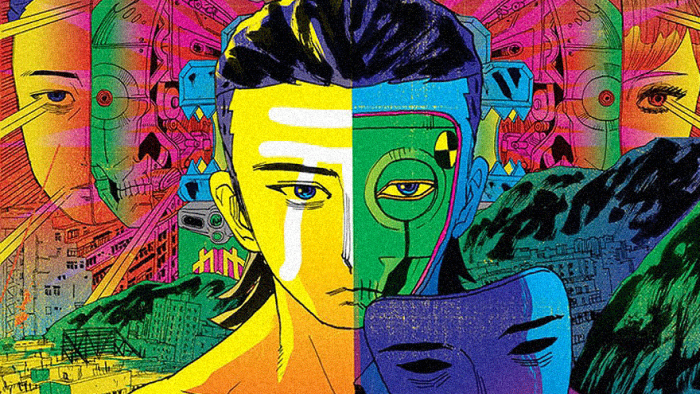

Image – Dragon’s Delusion, Kong Kee